Book Review: Into the World of the New Testament

Daniel Lynwood Smith has written a brief but highly informative and very readable introduction to the background of the New Testament. At just over 200 pages, it is a fraction the size of a typical New Testament introduction, and is divided into thirteen easily manageable chapters. Each provides a substantial overview of some aspect of the cultural context in which the New Testament was written. The style is consistently engaging, and the text manages to cover a lot of ground quite comfortably.

Following an introductory essay answering the question, ‘What Is the New Testament?’, there are three parts. The two chapters of the first part, ‘The Setting’, cover some of the political and religious background of, first, Jews in first-century Palestine, and second, Jews within the Roman Empire. The first chapter ends with a brief timeline from 722 BC to AD 135, the second with dates and full names of Roman Emperors down to Hadrian. These are helpful, and I suspect would be even more so if the reader knew they were there before starting the chapter.

These first three chapters are intended to be read in sequence as background for the rest of the book, but thereafter the chapters are by design relatively independent, and can be read in different orders. Part II, ‘The Cast of Characters’, comprises six chapters. The first covers John the Baptist and other denizens of the Judean wilderness. It is followed by an eclectic chapter presenting the Virgin Mary (largely about the place of women in that society), Herod the Great and his dynasty, the high priest Caiaphas, Pontius Pilate, and Rabbi Gamaliel (the first). Then there are chapters on Jesus, the disciples, ‘The Jews’ (cultural aspects of Second Temple Judaism, including the different sects), and Paul.

The final part, ‘Reading Old Words’, offers three chapters on topics that can cause confusion among the uninitiated. The first concerns the cultural associations of crucifixion in Jewish and Greco-Roman culture; the second, the ambiguity of the Greek word pistis (usually translated ‘faith’ or ‘faithfulness’); and the third, apocalyptic literature, with particular reference to Revelation. The book ends with a ‘Post-Script’ that briefly considers the canonical process leading to the New Testament, focusing especially on its relationship to the Old Testament by contrasting Marcion and Irenaeus.

A significant feature of the book is the inclusion of excerpts from many ancient sources outside the New Testament. An index of sources lists, besides the Old and New Testaments and a few references to the Apocrypha, around seventy Jewish and Greco-Roman sources cited in the course of the discussion.

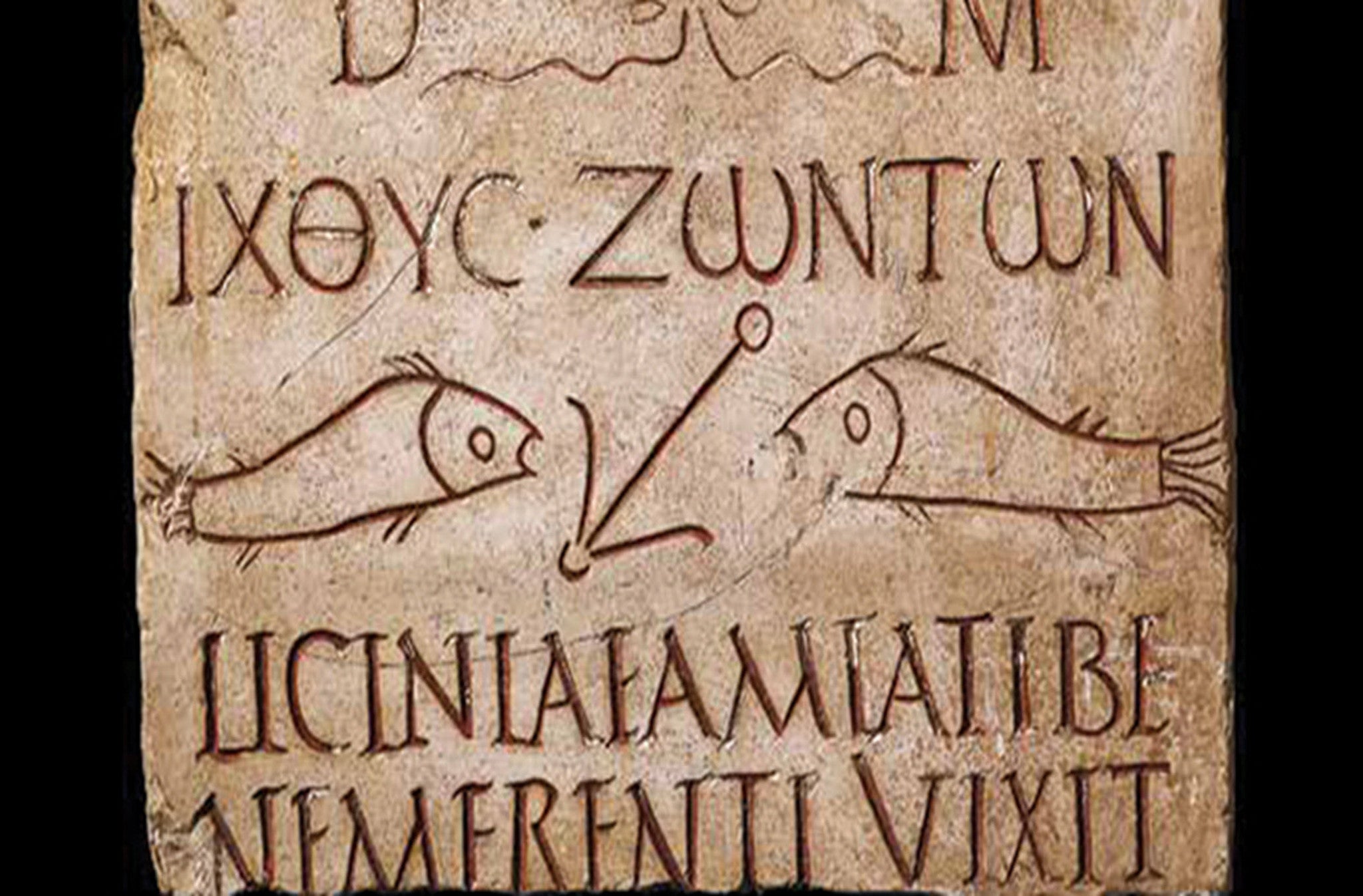

Each chapter begins with ‘Guiding Questions’ and one or more relevant quotes from the New Testament, and ends with an excellent annotated bibliography pointing to resources for following up the themes developed. In addition to the index of sources, there is a subject index, a pair of maps, a dozen or so black and white images scattered through the book, and a decent glossary. Terms listed in the glossary are highlighted throughout. Lecturers in New Testament should also note there is a helpful sample syllabus accessible via the book’s website (www.bloomsbury.com/uk/into-the-world-of-the-new-testament-9780567657022/).

This fine book is designed as a textbook for use alongside study of the New Testament text itself, but would also be an excellent resource for Bible study leaders and a useful start for anyone interested in improving their understanding of the background of the New Testament. The many quotations of other material should even appeal to those who have read other introductions, and the suggested further reading could be a good way to structure further self-study.

An excerpt of Into the World of the New Testament is printed on pp28-30 of this issue.

Leave a comment

Comments will be approved before showing up.