Intermarried: Survey and Book Review

You know you live in a culturally rich city (Sydney, in my case) when your children’s friends include a Chinese Polish Jew, a part-Greek with Australian Aboriginal roots, a Lebanese Russian, a Russian Indian, a Chinese Sudanese, and any number of Eurasians.

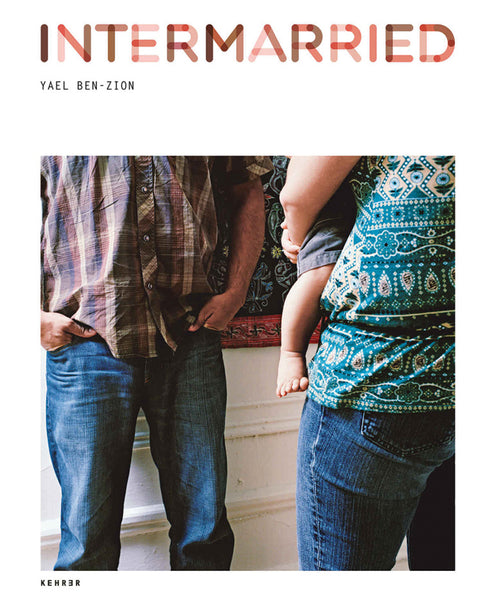

New York is even more well-known for being a cultural melting pot, and is the home of Yael Ben-Zion who has recently published the beautifully produced book, Intermarried. A photo-journal, it explores the phenomenon of racial and/or religious intermarriage, combining images with text from interviews with the participating couples.

An introductory essay by Maurice Berger points out that the book highlights the paradoxical strangeness and mundaneness of intermarriage; strangeness because it brings together two different worlds; mundaneness because to live together, eat together, raise children together, and do chores together are part of everyday married life everywhere. The photographs depict this powerfully: a mother dressing a child with different racial features; a mantelpiece with Hannukah candles around a Christmas wreath; family photos on the dresser with people of varying skin colour and style of dress; the Eiffel tower and Scottish tartan side by side on a child’s bedroom wall.

Another theme is the difference in attitude now and then. Ben-Zion includes a photo of a white man and black woman who married in New York in the 1950s, a time when most states in the US (though not New York) had anti-miscegenation laws preventing marriage between people of different race. It was not until 1967 that ‘state laws restricting interracial marriage were invalidated by the United States Supreme Court’ (Berger, p7). Another image shows the first census that allowed respondents to tick more than one box on the racial identity question; surprisingly, it was in the year 2000. The couples report that things are moving in the right direction, with mixed marriages becoming more socially accepted, though references to racism directed towards the couples and their children remain, sadly, all too frequent.

Other than racism, children and religion were the topics most frequently raised as difficult by the couples Ben-Zion interviewed, and things became particularly thorny when these were combined in the question ‘What religion will our child be?’. Children can be taught two languages, and claim two cultural heritages, but to be brought up in two religions is a different ballgame. Several of the couples interviewed belonged to the same religion despite different racial backgrounds, and so avoided this problem. For another, one spouse chose to convert. But for some it presented difficult and unavoidable decisions:

The biggest decision we are facing right now is whether to baptize our son. (p66)

When we found out that we have twin boys the question of circumcision inevitably came up. (p52)

One couple was even attempting to avoid the choice and raise their daughter in two faiths (p58). Given the mutually exclusive nature of most religions, this would rather undermine the effort to bring her up in either.

There is much in Intermarriage to give Christians pause for thought. Included is a quote from a judge presiding in an anti-miscegenation case in 1959, who opined:

Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, malay and red, and he placed them on separate continents… The fact that he separated the races shows that he did not intend for the races to mix. (p95)

Such claims sound laughable now (or perhaps make us weep), but we are all blinkered by attitudes of time and place. We should make every effort to not misrepresent God by dragging him in to bolster the prejudices of our own time and culture. However neither can this judge’s comment be considered representative of Christian thought, even historically. Christians have frequently been champions of racial equality in the face of extreme societal discrimination—William Wilberforce and Desmond Tutu are two well-known advocates.

Sensitive to its subject matter, the book is open and accepting to a fault. There is no hint of racial, religious, or even ‘form of marriage’ discrimination. Berger writes in his introduction that for most couples, marriage is ‘a matter of choice—to share their life together, in sickness and in health, to love and to cherish, from one day forward and as long as they see fit’ (p5).

Christians only have the luxury of wholehearted agreement with the first of these three: there is no place for racial discrimination in the church, and Christians should fight against it in wider society as far as they are able. In terms of intellectual religious discrimination, however, Christians—like members of most other religions—cannot maintain that all religions are equally true or valid and so cannot share the political correctness of Intermarried. Religion, taken seriously, sets the boundaries and direction of life: who are we, what is our purpose, how should we live? Marriage that joins people on different sides of such fundamental divides will be very difficult at best, for spouses will be constantly pulling in different directions.[1] Finally, the Christian view of marriage means that Christians must take issue with the idea that the nature of marriage can be altered and remain marriage. For a couple to commit to live together only ‘as long as they see fit’—that is, without the intention of life-long commitment—is quasi-marriage. Arguably, it is further from marriage than a de facto couple who move in together with the intention of lifelong commitment. As Heath and Adeney point out in this issue, marriage is more like a house that you are moving into, than a piece of land on which you can design any building you like, and marriage vows should reflect the house that is there: ‘Perhaps you can move some of the furniture around a bit, but there’s a lot you can’t modify—the fundamental nature and purposes of marriage aren’t up for negotiation.’[2] The intention of life-long commitment is one such structural necessity in the house.

Cross Cultural Marriage Survey

Inspired by Ben-Zion’s book and ‘intermarried’ friends, I decided to conduct my own survey, and ask married couples from different racial and/or cultural backgrounds about their experiences. Like Ben-Zion’s, the survey was fairly casual—small sample size, and with no particular attempt to be representative of the range of backgrounds or intermarried combinations across the community.[3] Unlike Ben-Zion’s, this survey was restricted to marriages where both spouses are Christian. I was interested in the joys and hardships of intermarriage, the impact of a common Christian belief, and what advice these couples might have for others considering marriage across cultural boundaries.

Background

Spouses from 13 cross-cultural marriages (CCM) completed the survey. Eleven of the 13 could be broadly categorised as Western-Asian marriages, the other two being European-Anglo, and Middle Eastern-Anglo combinations. Seven spouses were 1st generation Australians (born in Australia, but both parents born elsewhere).[4] The couples had been married on average 12 years (ranging from 1 to 23 years); and had on average 2.7 children. (The number of children ranged from 0 to 5, and their ages ranged from 0 to 17.)

Participants were asked to rate how different their spouse’s cultural background is to their own on a scale of 1 to 10 (where 1=No Different and 10=Completely Different). Seventy percent of the ratings fell in the ‘more different’ half of the scale, with an average rating of 6.4, and 7 and 8 being the most common ratings (range: 3-10).

Benefits of CCM

CCM couples were enthusiastic about the benefits of marrying across cultures. Spouses enjoyed increased exposure to new cultures, different foods, and travel opportunities. The expanded experiences CCM opened for children were particularly appreciated, such as second language and learning about different heritages.

Some couples, recognising that both their cultures had different strengths and weaknesses, took the opportunity to build a new family culture out of the ‘best bits’ of the cultures each person brought to the marriage. This extended to benefitting from the cultural values of extended family, such as the practical and financial support given in some cultures.

A common theme was that being married to someone from a different culture contributed greatly to the personal development of both knowledge and character. It helped to develop an understanding of different cultures, appreciate difference, increase cultural sensitivity and patience, and help people see things from different perspectives. This, in turn, helped people in mixed culture families connect with the wider multicultural community. It also forced people to recognise and evaluate their own cultural tendencies—tendencies that may have remained unexamined were they shared by both partners.

Some respondents pointed out that because they come from overtly different cultures, they don’t assume they will think the same on any given issue, and this makes them more prepared to work through differences that arise. This expectation of difference may be a strength CCMs enjoy over same-culture marriages, where differences will also arise, but where their very unexpectedness can add to the difficulty of dealing with them.

Hardships in CCMs

The difficulties survey participants reported that CCMs face can be grouped together into three categories. ‘Marital difficulties’ are those that concern the couple themselves. These include different goals and values, and the day-to-day differences in the cultural norms of how to run a household—anything from how to wash up to managing finances. Similarly, different cultures show and appreciate different ways of relating and showing love—obviously a key aspect of marriage. Couples were often unaware of these differences early on in marriage and as a result, miscommunication was common. Many responses therefore emphasised the need for patience and grace while working through the arduous process of identifying and evaluating cultural assumptions. One respondent pointed out that differences can remain latent for years, only surfacing when new circumstances arise, so this process is never fully complete.

Another difficulty identified was ignorance of the personal history of the spouse—the lack of ‘a sense of the place or wider family culture … and the influences on his formative years’, as one respondent put it. Sheer distance between the places childhoods were spent can rob couples of this source of understanding each other.

The other two difficult areas in CCM arose out of different assumptions and priorities relating to raising children and extended family.

Almost all respondents said that their cultural disparity became more obtrusive after having children. This included different expectations about how family life should look, gender roles in parenting, discipline, showing love, the importance of academic success, extracurricular activities, nutrition, and even nappy disposal! Like the day to day differences mentioned above, parenting decisions for these couples required more discussion and negotiation due to different cultural assumptions. But negotiations about how children should be brought up were even harder because of the fatigue and intensity being a parent brings.

Like child-raising, relationships with in-laws and other members of extended family are a notoriously fraught aspect of any marriage, but adding different cultural backgrounds to the mix exacerbates it further:

Families are very different, and managing the expectations of older generations was something we underestimated.

Couples who resolved differences to their own satisfaction, still sometimes faced pressure from extended family who were not privy to these negotiations, or who didn’t accept the decisions made by the couple. Respondents noted radically different expectations about family dynamics, and for some respondents, language barriers made even ordinary communicating hard, let alone resolving misunderstandings.

The perfect storm in CCMs develops when these two areas of conflict coalesce and couples face the child-rearing expectations of extended family—especially grandparents. As one respondent noted, ‘the cultural gap is even wider when you go back a generation’, and different expectations about children across culture and generation was a frequently reported source of family tension. Differing cultural expectations on child-raising led to ‘pressure from both sets of parents about how to raise kids the right way’. The expected level of involvement of grandparents in their grandchildren’s upbringing was often a source of contention, both in terms of how much time they should spend together, and how much say grandparents should have in how they will be raised.

Unlike their NY counterparts in Ben-Zion’s book, racism was only mentioned once as a particular trial a couple had faced, though another respondent with young children was concerned about how their children would deal with issues of identity and acceptance, given that they look different to both their parents. However, no respondents with older children mentioned this, which, together with the prevalence of mixed background children in Australia, is reason to hope these issues are not as severe as they might be, at least among the cultural combinations represented in the survey.

What I wish I knew

The survey asked CCM respondents about their expectations and whether, with the benefit of hindsight, there was anything they wished they had known before they married.

Asked to rate how accurate their premarital expectations were of what it would be like to marry across cultures, most people found their expectations to be more accurate than inaccurate.[5] However there were still areas where they felt they could have been better prepared. Several respondents reported underestimating just how much impact the cultural differences would have: ‘Culture affects you more than you think it will.’ This included differences between spouses, and also differences between families, where conflict between the couple and extended family often caused greater stress than anticipated.

Some wished they had entered the marriage with a more realistic understanding of the culture they were marrying into, and had made the effort to learn about it more broadly and not just through their partner. Others found their cultural understanding was adequate, but ‘would have liked more Christian input rather than culture specific’ information—better preparation to be gracious and patient; and not having expectations of changing their spouse.

Respondents were also invited to list any resources they had found helpful. Other than the Bible, the only resource mentioned (and it was mentioned repeatedly) was other cross-cultural couples, especially older ones who have worked through many difficulties already. For example:

Good to talk to others in CC marriages before you get married. We go to a church full of CC marriages which is a great support.

Christian impact

The final survey question asked how being Christian had made a difference to marriage across cultures. Some of the answers were things that would apply to any Christian marriage, but are all the more crucial in a CCM where misunderstandings are all too easy. These included helping people acknowledge and repent of sin; willingness to love self-sacrificially, and to forgive when wronged; and commitment to work through difficulties and stay together.

Other responses were particularly relevant to the cross-cultural situation. Several people noted that common goals of the Christian life help keep cultural differences in perspective:

It has given us a common foundation for our relationship that is independent of cultural background.

[T]hat which unites us is greater than our difference.

It would seem that because both spouses in the marriages I surveyed sought to live in accordance with the Bible, they were able to step back and evaluate their cultural assumptions against it:

The gospel allows us to extract ourselves from our culture and test both … cultures to see whether certain aspects are in line with the Bible.

Being Christian also seems to have grounded their identity and value in a context that is constantly challenging:

[I]t means your identity is fundamentally in Christ not in family background. That comforts us as a married couple, even during times when we are hurting and feel so different. It gives us a way to come back together and grow.

* * *

Cross cultural marriages have their own particular mix of joys and hardships. Sharing everyday life with someone from a different culture takes work, but as one respondent pointed out, every marriage involves mixing cultures to some degree. Every family has its own micro-culture, and ethnic background is not an insurmountable barrier to a good marriage, especially where couples share foundational beliefs about who they are and why they are here.

[1] Note however, that this intellectual discrimination does not extend to any kind of harm based on religious discrimination: disagreeing with someone and acting with harmful intent are completely different things. Christians, who are called upon to love their neighbour and even their enemy as themselves, might do the first, but not the second.

[2] Tim Adeney and Stuart Heath, ‘Marriage: What is it for?’ Case Quarterly, No.39 (2014) p8.

[3] My sample included fewer racial combinations than Ben-Zion’s. Eleven of the thirteen couples who responded were broadly Asian-Western, with slightly more Western husbands than wives. The very small and unrepresentative sample size means no comparisons could be made between different cultural combinations. The discussion should be taken at an anecdotal level.

[4] Interestingly, almost half the participants (11) themselves had parents who were born in different countries to each other.

[5] On a scale from 1 (‘Very Inaccurate’) to 10 (‘Very Accurate’), ratings ranged between 3 and 9, with an average of 6.8.

Leave a comment

Comments will be approved before showing up.