Archetypal Narratives & the Artist in the Body of Christ

We serve simultaneously as the actors and audience for that stage which Shakespeare perspicaciously identified as ‘all the world’. Powerful, archetypal narratives influence us deeply while we live out our stories and try to understand our place and purpose in the world. Narratives provide under-arching frameworks that help us make sense of our individual and corporate identities. Archetypal narratives underpin the drama of real life but also act as foundations for the art and media platforms that we listen to and look at. Although in this discussion I refer primarily to music, literature and film, these ideas also apply to other disciplines of art such as dance and the visual arts.

Archetypal narratives can be useful and harmful in Christian formation. Art synthesises and embodies the creative imagination of the artist as he or she references contemporary culture, beliefs, history, experiences and an existing body of work. Art can simultaneously reflect aspects of a culture, and create a product that will contribute to shaping or re-shaping that culture. The shaping and reshaping occur, in part, as an audience identifies with the archetypal narrative underpinning the art being displayed; or perhaps as they react against it.

Archetypes are platforms that can be used to edify or manipulate audiences. At best, audiences may be edified when archetypes are used to present the truth with integrity, and portray goodness as good. At worst, they serve as a platform for propaganda, where falsehood is treated as truth, and evil as good. The potential to influence an audience through art, as opposed to argument or research, is heightened because art is so often consumed in the context of entertainment and relaxation, where critical defences are likely to be down. This is further exacerbated by the relentless barrage of various forms of media made possible by technology. As media platforms evolve, active participation (for example through online gaming) expands, diversifies and accelerates the traditional influence of archetypal narratives. Censorship, even where desirable, is almost impossible. So much has changed since the beginning of the 20th century when private literature, messages from the pulpit and live performances of music, dance and drama still comprised most of the modes by which narratives were consumed and digested. The sheer frequency, volume and variety of modes by which people consume narratives today reduces their ability to digest and test how they will let those narratives influence them.

As James K A Smith has argued, we are constantly being influenced by what he terms ‘secular liturgies’ and ‘pedagogies of desire’—whether we are aware of it or not, and usually we are not. As a result:

it is not enough to equip our intellects to think rightly about the world. We also need to recruit our imaginations. Our hearts need to be captured by a vision … directed toward the Kingdom of God. Such a conversion of the imagination, I want to argue, is most powerfully accomplished through stories. [1]

Our society is saturated by messages that reflect hearts that are broken and minds that are darkened in their understanding. In order to offer compelling alternatives to secular liturgies, it would be valuable for Christian scholars, theologians, and artists to work together to identify how archetypal narratives can best be employed. Which archetypal narratives should be adopted as foundational for the art we create? How can those archetypal narratives be employed in consonance with a Christian worldview? How can they promote a desire for God’s kingdom?

Archetypal narratives are like skeletons waiting for artists to give them flesh. One archetypal narrative is ‘the quest’, in which a hero journeys through a series of challenges against evil opponents in search of treasure, such as a golden chalice or member of the opposite sex (traditionally a princess). The quest is, perhaps, the most entrenched archetypal narrative in our culture today.

The movie Shrek, C.S Lewis’ The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, and even the story of Israel’s exodus from Egypt are examples of the quest genre.[2] C.S Lewis demonstrates that the quest may be employed for the edification of children (and adults) in consonance with Christian belief. On the other hand the archetype can function in dissonance with Christian teachings, instead reinforcing worldly quests based on greed, pride and perverted notions of love and romance.

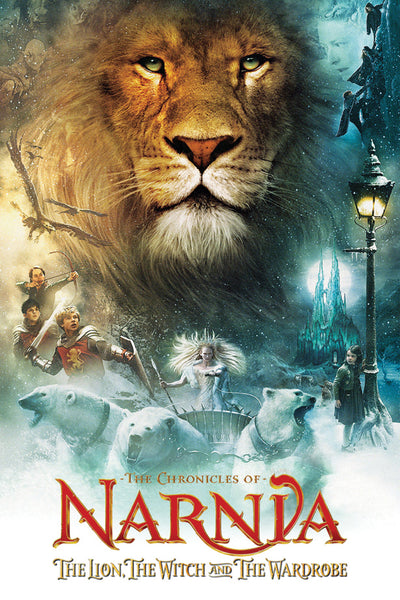

Another archetypal narrative is ‘redemption’. The redemption archetype presents a situation characterised by deepening despair for the plight of the main characters, averted only by the sacrifice of a central character. This archetype can act as a powerful tool and is seen in narratives such as The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, Les Miserables, A Tale of Two Cities, The Matrix, Deep Impact and the Harry Potter series. While the redemption archetype applied through art can be used in opposition or with indifference to Christianity, it is the central narrative of the Christian faith. It is, therefore, a good starting point for Christian artists searching for a foundation upon which to create their art.

Professor Trevor Hart has argued for the importance of artists and artistry as witness-bearers to Christ’s redemptive engagement with us as human creatures. Writing for Case, Hart wrote, ‘While the precise nature of art’s effect upon us remains a subject of complexity and dispute, we hardly need a degree in aesthetics to identify the effect when it happens, to realise its force and depth, and that it is something good for which we are mostly glad.’[3]

Using archetypal narratives as a tool, Christian artists have an opportunity to create works that reflect the ultimate narrative, that of Christ conquering death to save the world from its sin. Given that we are, to some extent, being conformed into the likeness of the art and entertainment that we consume, Christian artists have a responsibility to engage with and contribute to a future body of artistic work underpinned by the redemption archetype. We may also find that we can harness existing archetypal narratives, such as ‘the quest’, and propagate new archetypal narratives for the edification and formation of Christian men, women and children. Ideally, Christian artists will not be left to pursue this task alone. More fruit will be borne if artists are encouraged to work in partnership with the church and its para-organisations. Imagine pastors and artists equipping each other to reflect the Word of God through art, and together praying that God’s Spirit would turn hearts to Jesus. By supporting Christian artists there is hope that both the saved and unsaved will be challenged and shaped by Christ-inspired creativity.

So how might a Christian artist utilise an archetypal narrative to point their audience toward Jesus and everything that his Lordship means for humanity? Let me refer to my first attempt, printed on the next page.

In 2009, I set music to a poem I had written entitled Servitude. The result is a choral work featuring soprano and tenor soloists, with massed choir and orchestra. Servitude attempts to present an interweaving of the quest and redemption archetypal narratives.

The poem is a surreal and allegorical reflection of the brokenness of the world, but also the gateway for its redemption. One character, ‘the tall, pale man’, bases his identity on his ability to hang on to health and wealth as he struggles through a quest to find his own notion of purpose and his own way to paradise. By contrast, the redemption archetype is woven into the poem with a ‘little dark boy’ being saved by the sacrificial act of ‘his father’. In the poem the ‘gate’ symbolises the cross of Christ and the ‘lake’ and ‘garden’ symbolise the hope of heaven. The story is told musically too, using leitmotifs[4]—the practice of associating characters, events and emotions with musical motifs. Leitmotifs are embedded in both the orchestral and choral parts of the Servitude score to assist the lyrical narrative.

* * *

Not every Christian artist will have the same influence as C.S Lewis, Bono, Denzel Washington or George Frederic Handel, just as not every preacher will have comparable influence to Billy Graham, Dietrich Bonhoeffer or John Chapman. It is comforting to know that while God takes delight in the work of his people, His love and grace are not apportioned according to our success. From the least to the greatest, Christian artists can play their part in the body of Christ. Archetypal narratives are one tool which they can use as they go about their creative work.

[1] J.K.A. Smith, ‘Educating the Imagination’. Case Vol.31, 2012, p12.

[2] The Exodus can be understood as an interweaving of the quest and redemption archetypal narratives.

[3] Trevor Hart, ‘Creation, Incarnation and Redemption—In the Arts?’. Case Vol.16, 2008, p9.

[4] Wilhelm Richard Wagner pioneered the use of leitmotifs.

Leave a comment

Comments will be approved before showing up.